Saved By Stories

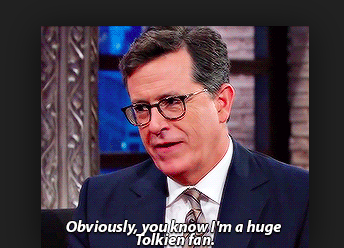

On Tuesday night, I watched Stephen Colbert interview the director and lead actors of the new movie “Tolkien” after a preview screening. I watched live as they all shared their stories of discovering a love for Tolkien’s works. Each discussed a different circumstance in their lives that led them to finding themselves in the books and movies, and Colbert summarized it quite nicely: he was “saved by stories.”

I won the ticket to this screening in a Tolkien trivia competition. I arrived alone, sat at a table with total strangers, and formed a small team. As the rounds went on, our little group floundered against the early frontrunner and best contender, a team more than twice our size. But we were determined. We closed the gap, formed a tie, and made it through the rest of the game plus three tiebreaker rounds before our victory.

It’s very rare that I feel as thrilled as I did that night. It’s not just that I was able to talk about my longest-lasting positive obsession, or even that I could prove my knowledge as someone who, thanks to my sex, has been questioned many times over whether I can be a “true nerd.”

What mattered the most to me that night was how people looked to me not as a source of random and useless facts from a world that doesn’t exist, or as someone whose obsessive thoughts make me strange, but as someone whose knowledge and passions mattered and could take me far. As the game got more heated and the questions got harder, I got shy about writing down answers. I thought I was looking too intense to my teammates, that they might think I was some sort of weirdo and not want to associate with me even if I could get the questions right.

I hesitated until one of my teammates encouraged me to just write down what was in my gut for the answers. He said that no matter what happened, he trusted my mind - and the others quickly joined in. Pencil flying over the paper, I was thought of as cool for remembering how to say “hobbits” in Sindarin (periannath, if you’re curious) and the process from the Silmarillion of how balrogs became balrogs.

After the victory, when we milled about the bar hoisting our prizes and eagerly chatting about the upcoming movie, I couldn’t have been happier. I showed every bit of knowledge I usually hide because I think it makes me seem strange, and people actually appreciated it and liked me for it. It was incredible, and the feeling resurfaced at the end of the screening, when the interview began to air.

Stephen Colbert recited poems from the books - Bilbo’s walking poem included - to general astonishment and applause from his audience at the Montclair Film Festival. It wasn’t strange that he had so much memorized or that he spoke in such depth about how the books helped him through his darkest times. It was brave, admirable, and all too familiar.

Losing myself in fantasy worlds and finding myself in them was the greatest pleasure of my childhood. Books took me away from obsessing over germs in the air or on my hands or already inside of me. They took me away from the times I was hungry because it was so much easier to not eat than to face my OCD head-on. They took me away from a life where adults who took pity on me were my only friends and brought me to a place where all sorts of people came together, no matter their past, and won.

No matter what happened, they won. It didn’t matter if they were facing a small skirmish or the war to end the Third Age, or clinging to the slopes of Mount Doom with nothing but hope and friendship. Sauron’s tower of Barad-Dur falls. The heroes win.

In all the times I’ve felt hopeless when faced with a life with OCD - even now, as I’m succeeding in keeping obsessive thoughts at bay, I know there will be times in the future when I relapse as I have before - Tolkien’s stories inspire me. And I was even more inspired to watch my museum experience come alive in the movie and see Tolkien’s life through his eyes, the incredible love and horrifying war that I can’t help but find in his works.

It’s my dream, one day, to do something similar - to turn pain into prose, to use stories to help others not feel quite so alone in their heads. And in the meantime, I’ll keep rereading and rewatching my favorite stories, starting with a rare edition of “The Two Towers” I was able to find in Hebrew.

Like Stephen Colbert and his interviewees, I was saved by stories. If the price of this is a passion that makes me jump for joy, I’m thrilled to find I am less ashamed of sharing it as time goes on. Just as I’ve found the stigma of nerdiness decreasing, I hope that one day, I can share more about my life with OCD openly and without shame or fear of losing respect or friendship.

In the words of Samwise Gamgee, the books and movies couldn’t carry my burden for me, but they carried me - and I’m proud to carry the passion and happiness they gave me forward into my life as a writer and beyond.

Ellie, a writer new to the Chicago area, was diagnosed with OCD at age 3. She hopes to educate others about her condition and end the stigma against mental illness.